A great way to get started with Stata is using its menus.

The first part of this Tutorial Series introduced you to Stata’s windows. You can now begin learning how to use Stata to work with data.

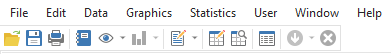

Across the top are 8 tabs: File, Edit, Data, Graphics, Statistics, User, Window, and Help.

We will not go through every option within the Stata menus. Instead, we’ll highlight a few options to get you started. In this article, we’ll start with three of the most useful menus: File, Data, and Help, along with those helpful icons under the menus.

In our next article, we’ll look at two more: Graphics and Statistics.

(more…)

So, you want to get started with Stata?

Good choice!

At The Analysis Factor we recommend first becoming proficient in one statistical software. Then once you’ve progressed up to learning Stage 3 skills, adding a second statistical software. Whether it’s your first, second, or 5th statistical software, Stata has a lot that makes it worth learning.

When I first started using Stata, I remember being confused by the variety of menus and windows, the strange syntax of the code, the way it handled datasets… and what the heck is a do file? (more…)

Many data sets are challenging and time consuming to work with because the data are seldom in an optimal format.

Many data sets are challenging and time consuming to work with because the data are seldom in an optimal format.

(more…)

In this 8-part tutorial, you will learn how to get started using Stata for data preparation, analysis, and graphing. This tutorial will give you the skills to start using Stata on your own. You will need a license to Stata and to have it installed before you begin.

In this 8-part tutorial, you will learn how to get started using Stata for data preparation, analysis, and graphing. This tutorial will give you the skills to start using Stata on your own. You will need a license to Stata and to have it installed before you begin.

(more…)

One of the difficult decisions in mixed modeling is deciding which factors are fixed and which are random. And as difficult as it is, it’s also very important. Correctly specifying the fixed and random factors of the model is vital to obtain accurate analyses.

Now, you may be thinking of the fixed and random effects in the model, rather than the factors themselves, as fixed or random. If so, remember that each term in the model (factor, covariate, interaction or other multiplicative term) has an effect. We’ll come back to how the model measures the effects for fixed and random factors.

Sadly, the definitions in many texts don’t help much with decisions to specify factors as fixed or random. Textbook examples are often artificial and hard to apply to the real, messy data you’re working with.

Here’s the real kicker. The same factor can often be fixed or random, depending on the researcher’s objective. (more…)

Of all the stressors you’ve got right now, accessing your statistical software from home shouldn’t be one of them. (You know, the one on your office computer).

We’ve gotten some updates from some statistical software companies on how they’re making it easier to access the software you have a license to or to extend a free trial while you’re working from home.

(more…)