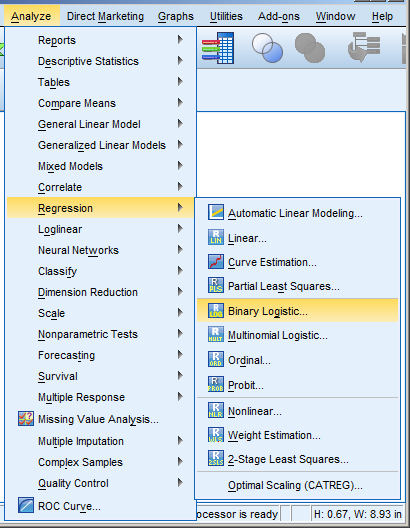

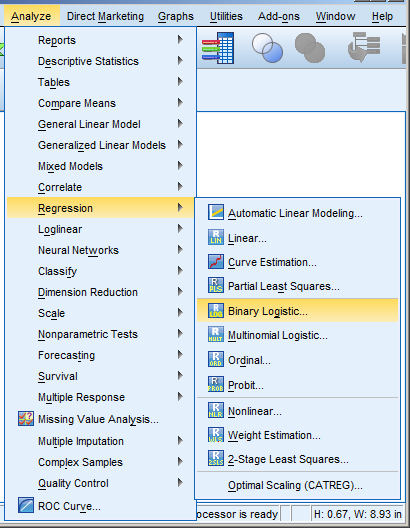

Need to run a logistic regression in SPSS? Turns out, SPSS has a number of procedures for running different types of logistic regression.

Some types of logistic regression can be run in more than one procedure. For some unknown reason, some procedures produce output others don’t. So it’s helpful to be able to use more than one.

Logistic Regression

Logistic Regression can be used only for binary dependent (more…)

Logistic Regression can be used only for binary dependent (more…)

Someone recently asked me if they need to learn R. In responding, it struck me that this is another way that learning a stat software package is like learning a new language.

Someone recently asked me if they need to learn R. In responding, it struck me that this is another way that learning a stat software package is like learning a new language.

The metaphor is extremely helpful for deciding when and how to learn a new stat software, and to keep you going when the going gets rough. (more…)

by Lucy Fike

We know that using SPSS syntax is an easy way to organize analyses so that you can rerun them in the future without having to go through the menu commands.

Using Python with SPSS makes it much easier to do complicated programming, or even basic programming, that would be difficult to do using SPSS syntax alone. You can use scripting programming in Python to create programs that execute automatically. (more…)

I sometimes get asked questions that many people need the answer to. Here’s one about non-parametric ANOVA in SPSS.

Question:

Is there a non-parametric 3 way ANOVA out there and does SPSS have a way of doing a non-parametric anova sort of thing with one main independent variable and 2 highly influential cofactors?

Quick Answer:

No.

Detailed Answer:

There is a non-parametric one-way ANOVA: Kruskal-Wallis, and it’s available in SPSS under non-parametric tests. There is even a non-paramteric two-way ANOVA, but it doesn’t include interactions (and for the life of me, I can’t remember its name, but I remember learning it in grad school).

But there is no non-parametric factorial ANOVA, and it’s because of the nature of interactions and most non-parametrics.

What it basically comes down to is that most non-parametric tests are rank-based. In other words, (more…)

One of the things I love about MIXED in SPSS is that the syntax is very similar to GLM. So anyone who is used to the GLM syntax has just a short jump to learn writing MIXED.

Which is a good thing, because many of the concepts are a big jump.

And because the MIXED dialogue menus are seriously unintuitive, I’ve concluded you’re much better off using syntax.

I was very happy a few years ago when, with version 19, SPSS finally introduced generalized linear mixed models so SPSS users could finally run logistic regression or count models on clustered data.

But then I tried it, and the menus are even less intuitive than in MIXED.

And the syntax isn’t much better. In this case, the syntax structure is quite different than for MIXED. (more…)

I received the following email from a reader after sending out the last article: Opposite Results in Ordinal Logistic Regression—Solving a Statistical Mystery.

And I agreed I’d answer it here in case anyone else was confused.

Karen’s explanations always make the bulb light up in my brain, but not this time.

With either output,

The odds of 1 vs > 1 is exp[-2.635] = 0.07 ie unlikely to be 1, much more likely (14.3x) to be >1

The odds of £2 vs > 2 exp[-0.812] =0.44 ie somewhat unlikely to be £2, more likely (2.3x) to be >2

SAS – using the usual regression equation

If NAES increases by 1 these odds become (more…)

Logistic Regression can be used only for binary dependent (more…)

Logistic Regression can be used only for binary dependent (more…)