There’s a common saying among pediatricians: children are not little adults. You can’t take a drug therapy that works in adults and scale it down to a kid-sized treatment.

There’s a common saying among pediatricians: children are not little adults. You can’t take a drug therapy that works in adults and scale it down to a kid-sized treatment.

Children are actively growing. Their livers metabolize drugs differently, and they have a stage of life called puberty that many of us have long forgotten.

Likewise, pilot studies are not little research studies. Please do not take a poorly funded clinical trial and try to sneak your inadequate sample size through peer review by calling it a pilot.

Pilot studies can serve one or more important purposes. Make sure you use them as intended rather than pretending they are kid-sized studies.

A pilot study has no value in and of itself. Its value is to serve the needs of a full-scale research study you or one of your colleagues hope to run in the future.

A Pilot Study helps Sample size Calculations

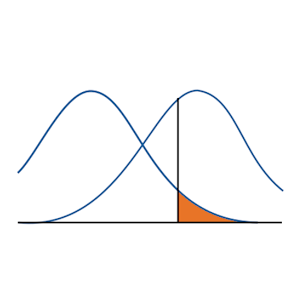

One of the best reasons to run a pilot study is it can help you estimate that elusive standard deviation– the one you need for your sample size justification.

Sometimes you can get a standard deviation from a previous study. But this is tricky. You will likely be extrapolating from a study run in a different part of the country, with a different demographic mix of subjects.

It is so much nicer to get an estimate of variation from the same place where the full-scale study will be run.

There are other things that influence your sample size justification. How many of your volunteers will read your consent form and then decline to take part? How many participants will start the study, but drop out?

You should factor in the refusal and drop-out rates in your sample size calculation.

The pilot study can help you estimate how quickly you can recruit participants. Do you get dozens every week, or do you need to wait a full month just to get a couple of volunteers? Will the study finish before the year is over or will it drag on past your retirement date?

A Pilot Study Helps Test Logistics

Another key reason to run a pilot study is it can help you test the study logistics. Can your busy clinic fit in the extra testing and measuring that your trial will need? Will your research team have the drugs ready to distribute in the right dosages? Will your data get entered properly into your research database?

A pilot study can help you vet your questionnaires. Do your participants understand what you are asking? Do they provide clear and unambiguous responses?

With Likert scale items, are respondents circling two numbers, leaving half of the questions blank, or writing detailed notes in the margin?

A pilot study can help you estimate resource requirements. How much time does an interview really take? It’s best to find out early if you have enough storage room for all the extra supplies your project will need.

How long does it take to prepare and mail out your surveys? Better to try with forty surveys before you have to mail out four thousand for the full study.

That interview that you plan for each participant– does it take five minutes or half an hour?

A Pilot Study Finds Unexpected Problems

The pilot study can help you discover unexpected problems. What kind of unexpected problems? Well, I don’t know, and you don’t know either. But “Murphy’s Law” guarantees that something unexpected will go wrong. Better for it to go wrong during the pilot study.

Also, keep in mind that what we ask our participants to endure with a new intervention may be too much to ask. Does your proposed research provoke participants to stage a sit-down strike? For that matter, does it cause a riot among your staff? It is better to find out with a ten-thousand-dollar pilot before starting a million-dollar clinical trial.

How Big Should your Pilot Study be?

Everyone wants to know how big your pilot study needs to be. There is no one-size-fits-all answer. If your main purpose is to get a quantitative measure (a standard deviation, a refusal rate, a drop-out rate) then make the pilot big enough to produce a reasonably narrow confidence interval for that measure.

But if your primary goal is to test the study logistics or identify unexpected problems, you might be able to use a smaller sample. Make it big enough to stress the capacity of your research team and to root out any unexpected problems. Here, “big enough” is a judgement call.

Running the pilot without a control group

If you are running a clinical trial or intervention study, you might consider dispensing with the control group in your pilot. What? No control group? That seems like heresy.

You do lose the ability to test your research hypothesis. But your pilot is not a kid-sized version of a bigger study. Admit it. You really didn’t hope to get any power or precision anyway with the small size of your pilot study. So why bother?

Consider dispensing with the control group if you already have a lot of experience providing the intervention.

Are your general protocols solid, but you need to test for problems with a new treatment? If so, it might make more sense to put all your eggs in one basket and double the number of volunteers in your pilot who are getting the new treatment.

Summary

A pilot study is not a label you slap on when you know the sample size is too small. You run a pilot study to get data you need to justify the sample size in a future large-scale study. Or maybe you run a pilot study to test the logistics of that future large-scale study. Or maybe you run a pilot to identify unexpected problems before you invest money in that future large-scale study.

In any case, a pilot study exists not for itself but only to serve the needs of a future research study.

By Steve Simon

About the Author

Steve Simon works as an independent statistical consultant and as a part-time faculty member in the Department of Biomedical and Health Informatics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He has previously worked at Children’s Mercy Hospital, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and Bowling Green State University.

Steve Simon works as an independent statistical consultant and as a part-time faculty member in the Department of Biomedical and Health Informatics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He has previously worked at Children’s Mercy Hospital, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and Bowling Green State University.

Steve has over 90 peer-reviewed publications, four of which have won major awards. He has written one book, Statistical Evidence in Medical Trials, and is the author of a major website about Statistics, Research Design, and Evidence Based Medicine, www.pmean.com. One of his current areas of interest is using Bayesian models to forecast patient accrual in clinical trials. Steve received a Ph.D. in Statistics from the University of Iowa in 1982.

If you don’t run a control group in your pilot, can you assume the SD is the sane in the control group as the treatment? My guess is the treatment affects both the mean and SD so we cannot assume it will be the sane.

If you have a reason to believe the sd is smaller in the control group and you can come up with a good estimate for that for your power analysis, that’s fine. The idea of the pilot is to get some numbers to work with.