One of those “rules” about statistics you often hear is that you can’t interpret a main effect in the presence of an interaction.

Stats professors seem particularly good at drilling this into students’ brains.

Unfortunately, it’s not true.

At least not always.

This is one of those situations where I caution researchers to think about their data and what makes sense, rather than memorize a rule.

When interactions do make main effects nonsensical

Let me start with a situation in which the rule holds, so that you can see why it is important to consider.

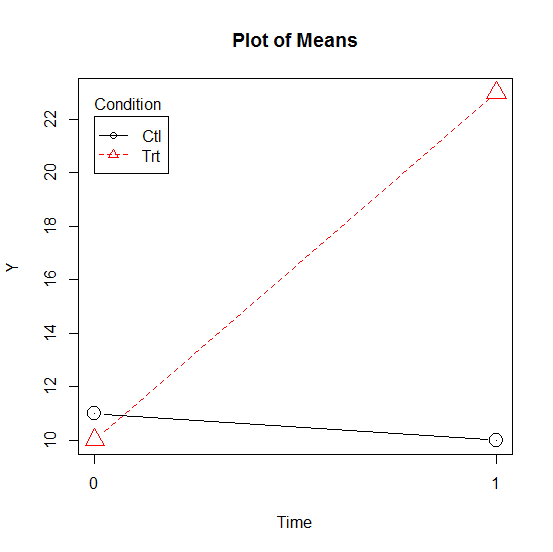

Consider this simple interaction between two categorical predictors: Time and Condition.

At baseline (Time=0) there is no difference in the mean of outcome variable Y for the two groups.

I’m just going to assume that that difference is not statistically significant, because the means are right on top of each other. But in a real data output, you’d want to verify this with a simple effects tests.

But there is clearly an interaction here–there was a large change in the mean of Y for the treatment group, but not the control.

This is a perfect example of a case where both main effects will be significant, but they’re not meaningful.

For example, the main effect for Condition will compare the height of the red dotted line to the height of the black solid line. Assuming equal sample sizes , those heights will be compared halfway between time 0 and 1.

Again, assuming adequate power, that difference probably will be significant. But it’s not a meaningful main effect.

A main effect says that there is a difference between the group means, regardless of time.

Sure, if you average it out, that may be technically true. But it’s pretty clear that’s only true on average across the time points because of the big difference at Time 1. It’s not true at each time point. So to say that the means generally differ across conditions, regardless of time, isn’t really accurate.

This is sometimes referred to the interaction driving the main effects and this particular example is why your stat teacher doesn’t want you to blindly say that the significant main effect means anything.

When interactions don’t affect main effects

But of course, meaningful main effects can exist even in the presence of an interaction.

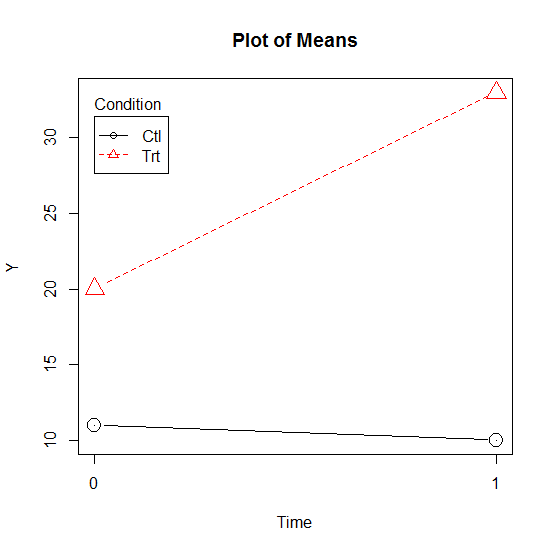

Take a very similar situation, with one important difference.

The interaction itself in the following graph is identical to the one above. The difference in means for the red triangles is once again 13 points, whereas the control group’s mean difference is negligible.

But the placement of the means is farther apart.

What makes the main effect meaningful here, despite the interaction, is that the treatment group’s mean is always higher than the control group’s. Even at Time=0.

That’s a meaningful main effect. It’s saying regardless of what is happening over time, the treatment group really does generally have higher means, regardless of when it’s measured.

Failing to mention this main effect, assuming it’s theoretically important, would be a shame. You’re missing the fact that the treatment group not only changed more, but started higher.

That’s a different situation than the first one, and you need to communicate that.

So when you have both a significant main effect and a significant interaction, stop and examine the results. Don’t assume the main effect is meaningless. It may be important.

Hey Karen,

I just found your article, and I while I usally find them to be very helpful, I struggle a little here:

I guess you are describing a case for a classical ANOVA?

Because, in the case of linear regression, the main effect (e.g., of X1) of one of two predictors involved in an interaction term (e.g. X1*X2) is the effect where the other predictor = 0.

A brief example: Consider X1 to be temperature with -5 to 5 degrees and X2 to be a dummy with 0 = treatment a and 1 = treatment b while Y would be growth of bacteria.

When you have an interaction of X1 and X2, the main effect of e.g. X1 would be the effect of temperature on bacterial growth for treatment group 0. Vice versa, the main effect estimate for differences between group 0 and 1 (X2) would be the difference when temperature would be at 0!

Thus, there would be no “average difference between the lines” or alike.

What do you think?

Thanks and best wishes

Martin

Hi Martin,

Yes, absolutely. The regression coefficients you’re describing are not actually main effects if the categorical variable in an interaction is dummy coded and/or numeric predictors aren’t centered.

Those are called marginal or simple effects.

You can change the scaling of the variables though to get main effects, or get them through marginal means in some cases.

Obviously, that isn’t true.

The main effect is determined by the average difference between control and treatment, without considering interaction. Therefore, regardless of whether the interaction is significant or not, the average difference between control and treatment is important. However, when the interaction is significant, the difference between the control and group is not constant, and we cannot interpret it when the interaction is present.

Hi Mehdi,

It’s true that you would interpret and report that main effect differently in the presence of an interaction. You could say, “X1 alone does have an effect, though the size of the effect can be as small as A to B (along with confidence intervals). On average, the size of that effect is C.” That’s very different though, that the usual advice which is to say, “we can’t tell at all whether there even is any effect of X1 so we’ll completely ignore it.”

1)You don’t test for baseline as gerro mentioned above. It is pointless because at baseline randomisation ensures that any difference is likeli to due to randomness therefore your test of null hypothesis i.e., H0= there is no group differences is actually don’t have a stand

2) When you have a study design like this, your ideal model to estimate the main effect is :

time1 score = intercept + baseline score + treatmentgroup + error

This gives you the main effect of intervention.

Is there a statistical test that we could perform that would justify not interpreting a significant interaction, allowing us to interpret only the individual main effects?

Thanks!

I still don’t understand why the main effect is more important in the second example. In the second example, the main effect of the condition would be the average of the two simple effects of condition (assuming equal sample sizes). So, the main effect of the condition would be roughly (10+25/2), or 17.5. I get why one would emphasize that the two simple effects are in the same direction. If the simple effects are both significant, that would also be important to discuss. But, in the second example, the main effect is still an average of two significantly different effects. What is the point in reporting the effect of the condition when time=.5? Again, I understand the difference in interpreting the main effect when there is a “cross-over” and when there isn’t. For example, the main effect of the condition would be 0 and pretty useless if the lines looked like a perfect X. I just still do not understand why you would interpret the main effect of one variable unless the average value of the variable it is interacting with is of theoretical importance.

Previously I had not understood why in the presence of interactions the main effects aren’t interesting, and the first example is quite explanatory.

Anyway, now I think that main effects aren’t interesting even in the second example. There, Trt*1 > Trt*2 > Ctr*1 = Ctr*2. So the comparisons of the interactions already shows that all Trt > all Crt.

In fact, the main effects could be very interesting in the second example. They reveal that the two groups were different at baseline in regards to the outcome. Depending on the study design this could indicate a flawed randomization, or selection bias, among other things.

One never tests differences at baseline in randomized trials. It’s pure nonsense. Randomization ensures that all subjects come from a single population. So even, if the differences are statistically significant, it’s nothing but an artefact (it’s not impossible to sample very different observations into 2 groups from the same population). If the randomization if flawed, no test can show that. It’s procedural problem, not statistical. The opposite holds in non-randomized trials, where the differences at baseline come likely from two different populations. Then, the Lord’s paradox is almost certain.

Good afternoon,

I have always been taught that if a main/interaction effect is not sig then you should not use the post hoc pairwise comparisons even if significant. Hopkins suggests that planned contrasts of this kind are acceptable and we can use them. What is the ‘correct’ answer and which resources would help in understanding this matter?

Many thanks

Nice.