Multinomial logistic regression is an important type of categorical data analysis. Specifically, it’s used when your response variable is nominal: more than two categories and not ordered.

Multinomial logistic regression is an important type of categorical data analysis. Specifically, it’s used when your response variable is nominal: more than two categories and not ordered.

(more…)

Regression models

Member Training: Multinomial Logistic Regression

Member Training: Centering

Centering variables is common practice in some areas, and rarely seen in others. That being the case, it isn’t always clear what are the reasons for centering variables.

Centering variables is common practice in some areas, and rarely seen in others. That being the case, it isn’t always clear what are the reasons for centering variables.  Is it only a matter of preference, or does centering variables help with analysis and interpretation? (more…)

Is it only a matter of preference, or does centering variables help with analysis and interpretation? (more…)

Member Training: Analyzing Likert Scale Data

Is it really ok to treat Likert items as continuous?

Is it really ok to treat Likert items as continuous?  And can you just decide to combine Likert items to make a scale? Likert-type data is extremely common—and so are questions like these about how to analyze it appropriately. (more…)

And can you just decide to combine Likert items to make a scale? Likert-type data is extremely common—and so are questions like these about how to analyze it appropriately. (more…)

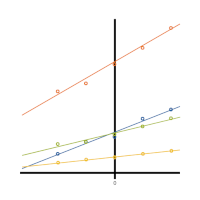

The Difference Between R-squared and Adjusted R-squared

When is it important to use adjusted R-squared instead of R-squared?

R², the Coefficient of Determination, is one of the most useful and intuitive statistics we have in linear regression.

It tells you how well the model predicts the outcome and has some nice properties. But it also has one big drawback.

Member Training: Assumptions of Linear Models

What are the assumptions of linear models? If you compare two lists of assumptions, most of the time they’re not the same.

What are the assumptions of linear models? If you compare two lists of assumptions, most of the time they’re not the same.

(more…)

When Linear Models Don’t Fit Your Data, Now What?

When your dependent variable is not continuous, unbounded, and measured on  an interval or ratio scale, linear models don’t fit. The data just will not meet the assumptions of linear models. But there’s good news, other models exist for many types of dependent variables.

an interval or ratio scale, linear models don’t fit. The data just will not meet the assumptions of linear models. But there’s good news, other models exist for many types of dependent variables.

Today I’m going to go into more detail about 6 common types of dependent variables that are either discrete, bounded, or measured on a nominal or ordinal scale and the tests that work for them instead. Some are all of these.