Proportion and percentage data are tricky to analyze.

Much like count data, they look like they should work in a linear model.

They’re numeric. They’re often continuous.

And sometimes they do work. Some proportion data do look normally distributed so estimates and p-values are reasonable.

But more often they don’t. So estimates and p-values are a mess. Luckily, there are other options. (more…)

By Manolo Romero Escobar

If you already know the principles of general linear modeling (GLM) you are on the right path to understand Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

As you could see from my previous post, SEM offers the flexibility of adding paths between predictors in a way that would take you several GLM models and still leave you with unanswered questions.

It also helps you use latent variables (as you will see in future posts).

GLM is just one of the pieces of the puzzle to fit SEM to your data. You also need to have an understanding of:

(more…)

Like the chicken and the egg, there’s a question about which comes first: run a model or check assumptions? Unlike the chicken’s, the model’s question has an easy answer.

There are two types of model assumptions in a statistical model. Some are distributional assumptions about the errors. Examples include independence, normality, and constant variance in a linear model.

Others are about the form of the model. They include linearity and (more…)

Others are about the form of the model. They include linearity and (more…)

by Manolo Romero Escobar

General Linear Model (GLM) is a tool used to understand and analyse linear relationships among variables. It is an umbrella term for many techniques that are taught in most statistics courses: ANOVA, multiple regression, etc.

In its simplest form it describes the relationship between two variables, “y” (dependent variable, outcome, and so on) and “x” (independent variable, predictor, etc). These variables could be both categorical (how many?), both continuous (how much?) or one of each.

Moreover, there can be more than one variable on each side of the relationship. One convention is to use capital letters to refer to multiple variables. Thus Y would mean multiple dependent variables and X would mean multiple independent variables. The most known equation that represents a GLM is: (more…)

In the last post, we examined how to use the same sample when running a set of regression models with different predictors.

Adding a predictor with missing data causes cases that had been included in previous models to be dropped from the new model.

Using different samples in different models can lead to very different conclusions when interpreting results.

Let’s look at how to investigate the effect of the missing data on the regression models in Stata.

The coefficient for the variable “frequent religious attendance” was negative 58 in model 3 and then rose to a positive 6 in model 4 when income was included. Results (more…)

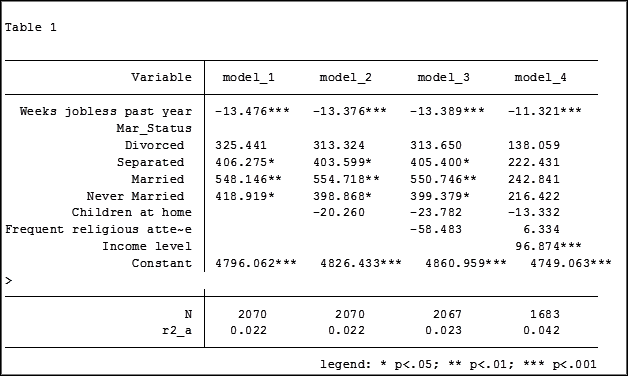

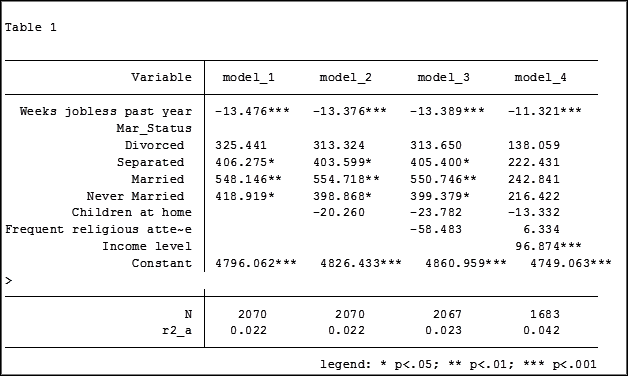

In my last article, Hierarchical Regression in Stata: An Easy Method to Compare Model Results, I presented the following table which examined the impact several predictors have on one’ mental health.

At the bottom of the table is the number of observations (N) contained within each sample.

The sample sizes are quite large. Does it really matter that they are different? The answer is absolutely yes.

Fortunately in Stata it is not a difficult process to use the same sample for all four models shown above.

Some background info:

As I have mentioned previously, Stata stores results in temp files. You don’t have to do anything to cause Stata to store these results, but if you’d like to use them, you need to know what they’re called.

To see what is stored after an estimation command, use the following code:

ereturn list

After a summary command:

return list

One of the stored results after an estimation command is the function e(sample). e(sample) returns a one column matrix. If an observation is used in the estimation command it will have a value of 1 in this matrix. If it is not used it will have a value of 0.

Remember that the “stored” results are in temp files. They will disappear the next time you run another estimation command.

The Steps

So how do I use the same sample for all my models? Follow these steps.

Using the regression example on mental health I determine which model has the fewest observations. In this case it was model four.

I rerun the model:

regress MCS weeks_unemployed i.marital_status kids_in_house religious_attend income

Next I use the generate command to create a new variable whose value is 1 if the observation was in the model and 0 if the observation was not. I will name the new variable “in_model_4”.

gen in_model_4 = e(sample)

Now I will re-run my four regressions and include only the observations that were used in model 4. I will store the models using different names so that I can compare them to the original models.

My commands to run the models are:

regress MCS weeks_unemployed i.marital_status if in_model_4==1

estimates store model_1a

regress MCS weeks_unemployed i.marital_status kids_in_house if in_model_4==1

estimates store model_2a

regress MCS weeks_unemployed i.marital_status kids_in_house religious_attend if in_model_4==1

estimates store model_3a

regress MCS weeks_unemployed i.marital_status kids_in_house religious_attend income if in_model_4==1

estimates store model_4a

Note: I could use the code if in_model_4 instead of if in_model_4==1. Stata interprets dummy variables as 0 = false, 1 = true.

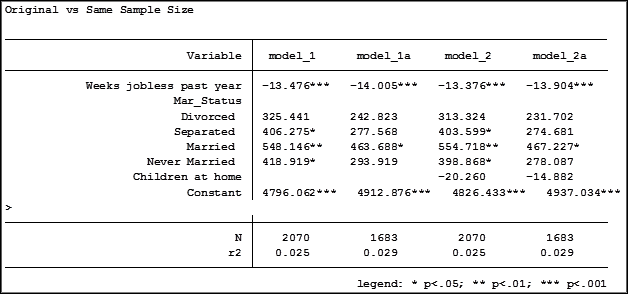

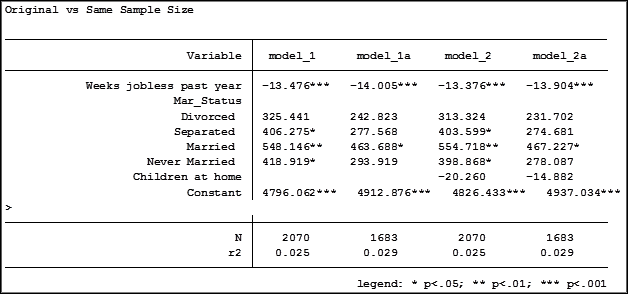

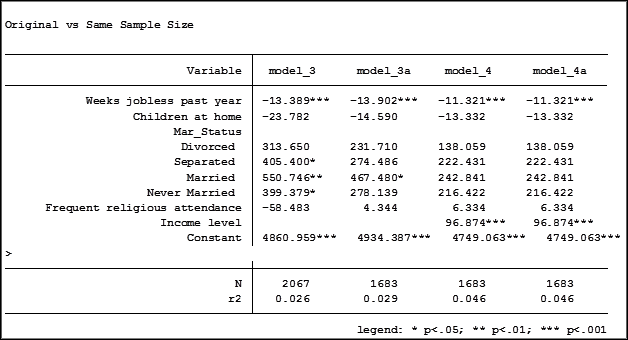

Here are the results comparing the original models (eg. Model_1) versus the models using the same sample (eg. Model_1a):

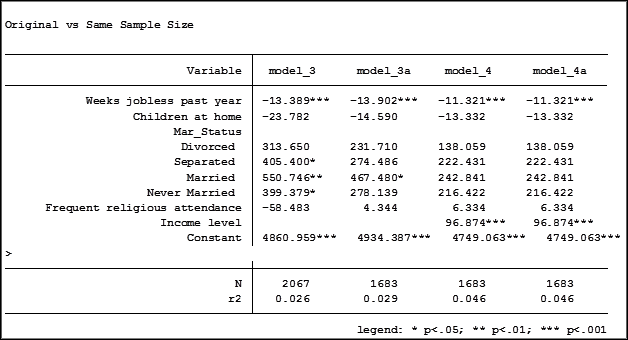

Comparing the original models 3 and 4 one would have assumed that the predictor variable “Income level” significantly impacted the coefficient of “Frequent religious attendance”. Its coefficient changed from -58.48 in model 3 to 6.33 in model 4.

That would have been the wrong assumption. That change is coefficient was not so much about any effect of the variable itself, but about the way it causes the sample to change via listwise deletion. Using the same sample, the change in the coefficient between the two models is very small, moving from 4 to 6.

Jeff Meyer is a statistical consultant with The Analysis Factor, a stats mentor for Statistically Speaking membership, and a workshop instructor. Read more about Jeff here.