A normal probability plot is extremely useful for checking normality assumptions. It’s more precise than a histogram, which can’t pick up subtle deviations. And yet it doesn’t suffer from too much power from large samples with tiny departures from normality or too little power from small samples with large departures from normality, as do tests like Shaprio-Wilkes.

A normal probability plot is extremely useful for checking normality assumptions. It’s more precise than a histogram, which can’t pick up subtle deviations. And yet it doesn’t suffer from too much power from large samples with tiny departures from normality or too little power from small samples with large departures from normality, as do tests like Shaprio-Wilkes.

The biggest problem with a normal probability plot is that it’s hard to read, especially if you’re not used to them. So let’s take a moment and walk through exactly how they work and what they tell you.

There are two versions of normal probability plot: Q-Q and P-P. I’ll start with the Q-Q. (more…)

You might be surprised to hear that not only can linear regression fit lines between a response variable Y and one or more predictor variables, X, it can fit curves too. There are many ways to do this, but the simplest is by adding a polynomial term.

So what is a polynomial term and how do you know you need one?

The linear parameters in a regression model

A linear regression model has a few key parameters. These include the intercept coefficient, the slope coefficient, and the residual variance.

That intercept defines the height of the regression line. It does so by measuring the height of the line at one specific point: when all X = 0.

The slope defines how much Y differs, on average, for each one unit difference in X. In other words, it measures the constant relationship between X and Y. Yes, there can be multiple Xs and each one has its own slope.

A polynomial term–a quadratic (squared) or cubic (cubed) term turns a linear regression model into a curve.

(more…)

No matter what statistical model you’re running, you need to take the same steps. The order and the specifics of  how you do each step will differ depending on the data and the type of model you use.

how you do each step will differ depending on the data and the type of model you use.

These steps are in 4 phases. Most people think of only the third as modeling. But the phases before this one are fundamental to making the modeling go well. It will be much, much easier, more accurate, and more efficient if you don’t skip them.

And there is no point in running the model if you skip the last phase. That’s where you communicate the results.

I’ve found that if I think of them all as part of the analysis, the modeling process is faster, easier, and makes more sense.

Phase 1: Define and Design

In the first five steps of running the model, the object is clarity. You want to make everything as clear as possible to yourself. The clearer things are at this point, the smoother everything will be. (more…)

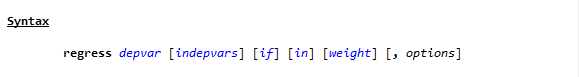

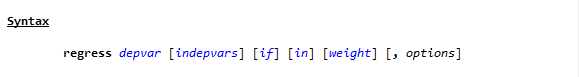

If you’ve tried coding in Stata, you may have found it strange. The syntax rules are straightforward, but different from what I’d expect.

I had experience coding in Java and R before I ever used Stata. Because of this, I expected commands to be followed by parentheses, and for this to make it easy to read the code’s structure.

Stata does not work this way.

An Example of how Stata Code Works

To see the way Stata handles a linear regression, go to the command line and type

h reg or help regress

You will see a help page pop up, with this Syntax line near the top.

(If you need a refresher on getting help in Stata, watch this video by Jeff Meyer.)

This is typical of how Stata code looks. (more…)

Regression is one of the most common analyses in statistics. Most of us learn it in grad school, and we learned it in a specific software. Maybe SPSS, maybe another software package. The thing is, depending on your training and when you did it, there is SO MUCH to know about doing a regression analysis in SPSS.

Regression is one of the most common analyses in statistics. Most of us learn it in grad school, and we learned it in a specific software. Maybe SPSS, maybe another software package. The thing is, depending on your training and when you did it, there is SO MUCH to know about doing a regression analysis in SPSS.

(more…)

I recently received a great question in a comment about whether the assumptions of normality, constant variance, and independence in linear models are about the errors, εi, or the response variable, Yi.

I recently received a great question in a comment about whether the assumptions of normality, constant variance, and independence in linear models are about the errors, εi, or the response variable, Yi.

The asker had a situation where Y, the response, was not normally distributed, but the residuals were.

Quick Answer: It’s just the errors.

In fact, if you look at any (good) statistics textbook on linear models, you’ll see below the model, stating the assumptions: (more…)

A normal probability plot is extremely useful for checking normality assumptions. It’s more precise than a histogram, which can’t pick up subtle deviations. And yet it doesn’t suffer from too much power from large samples with tiny departures from normality or too little power from small samples with large departures from normality, as do tests like Shaprio-Wilkes.

A normal probability plot is extremely useful for checking normality assumptions. It’s more precise than a histogram, which can’t pick up subtle deviations. And yet it doesn’t suffer from too much power from large samples with tiny departures from normality or too little power from small samples with large departures from normality, as do tests like Shaprio-Wilkes.