Generalized linear models, linear mixed models, generalized linear mixed models, marginal models, GEE models. You’ve probably heard of more than one of them and you’ve probably also heard that each one is an extension of our old friend, the general linear model.

This is true, and they extend our old friend in different ways, particularly in regard to the measurement level of the dependent variable and the independence of the measurements. So while the names are similar (and confusing), the distinctions are important.

It’s important to note here that I am glossing over many, many details in order to give you a basic overview of some important distinctions. These are complicated models, but I hope this overview gives you a starting place from which to explore more. (more…)

“Because mixed models are more complex and more flexible than the general linear model, the potential for confusion and errors is higher.”

– Hamer & Simpson (2005)

Linear Mixed Models, as implemented in SAS’s Proc Mixed, SPSS Mixed, R’s LMER, and Stata’s xtmixed, are an extension of the general linear model. They use more sophisticated techniques for estimation of parameters (means, variances, regression coefficients, and standard errors), and as the quotation says, are much more flexible.

Here’s one example of the flexibility of mixed models, and its resulting potential for confusion and error. (more…)

Of all the concepts I see researchers struggle with as they start to learn high-level statistics, the one that seems to most often elicit the blank stare of incomprehension is the Covariance Matrix, and its friend, the Covariance Structure.

And since understanding them is fundamental to a number of statistical analyses, particularly Mixed Models and Structural Equation Modeling, it’s an incomprehension you can’t afford.

So I’m going to explain what they are and how they’re not so different from what you’re used to. I hope you’ll see that once you get to know them, they aren’t so scary after all.

What is a Covariance Matrix?

There are two concepts inherent in a covariance matrix–covariance and matrix. Either one can throw you off.

Let’s start with matrix. If you never took linear algebra, the idea of matrices can be frightening. (And if you still are in school, I highly recommend you take it. Highly). And there are a lot of very complicated, mathematical things you can do with matrices.

But you, a researcher and data analyst, don’t need to be able to do all those complicated processes to your matrices. You do need to understand what a matrix is, be able to follow the notation, and understand a few simple matrix processes, like multiplication of a matrix by a constant.

The thing to keep in mind when it all gets overwhelming is a matrix is just a table. That’s it.

A Covariance Matrix, like many matrices used in statistics, is symmetric. That means that the table has the same headings across the top as it does along the side.

Start with a Correlation Matrix

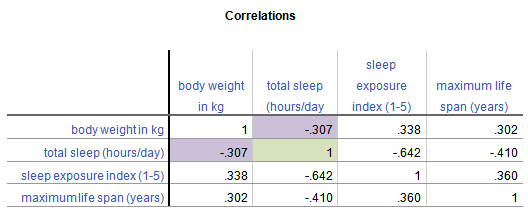

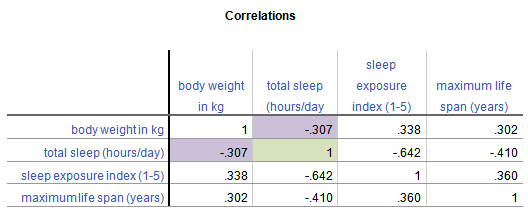

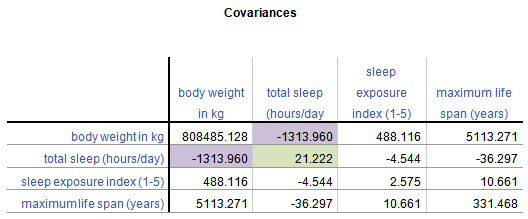

The simplest example, and a cousin of a covariance matrix, is a correlation matrix. It’s just a table in which each variable is listed in both the column headings and row headings, and each cell of the table (i.e. matrix) is the correlation between the variables that make up the column and row headings. Here is a simple example from a data set on 62 species of mammal:

From this table, you can see that the correlation between Weight in kg and Hours of Sleep, highlighted in purple, is -.307. Smaller mammals tend to sleep more.

You’ll notice that this is the same above and below the diagonal. The correlation of Hours of Sleep with Weight in kg is the same as the correlation between Weight in kg and Hours of Sleep.

Likewise, all correlations on the diagonal equal 1, because they’re the correlation of each variable with itself.

If this table were written as a matrix, you’d only see the numbers, without the column headings.

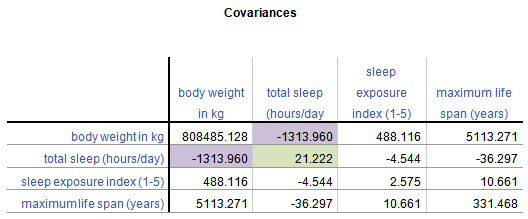

Now, the Covariance Matrix

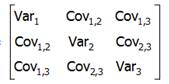

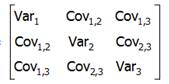

A Covariance Matrix is very similar. There are really two differences between it and the Correlation Matrix. It has this form:

First, we have substituted the correlation values with covariances.

Covariance is just an unstandardized version of correlation. To compute any correlation, we divide the covariance by the standard deviation of both variables to remove units of measurement. So a covariance is just a correlation measured in the units of the original variables.

Covariance, unlike correlation, is not constrained to being between -1 and 1. But the covariance’s sign will always be the same as the corresponding correlation’s. And a covariance=0 has the exact same meaning as a correlation=0: no linear relationship.

Because covariance is in the original units of the variables, variables on scales with bigger numbers and with wider distributions will necessarily have bigger covariances. So for example, Life Span has similar correlations to Weight and Exposure while sleeping, both around .3.

But values of Weight vary a lot (this data set contains both Elephants and Shrews), whereas Exposure is an index variable that ranges from only 1 to 5. So Life Span’s covariance with Weight (5113.27) is much larger than than with Exposure (10.66).

Second, the diagonal cells of the matrix contain the variances of each variable. A covariance of a variable with itself is simply the variance. So you have a context for interpreting these covariance values.

Once again, a covariance matrix is just the table without the row and column headings.

What about Covariance Structures?

Covariance Structures are just patterns in covariance matrices. Some of these patterns occur often enough in some statistical procedures that they have names.

You may have heard of some of these names–Compound Symmetry, Variance Components, Unstructured, for example. They sound strange because they’re often thrown about without any explanation.

But they’re just descriptions of patterns.

For example, the Compound Symmetry structure just means that all the variances are equal to each other and all the covariances are equal to each other. That’s it.

It wouldn’t make sense with our animal data set because each variable is measured on a different scale. But if all four variables were measured on the same scale, or better yet, if they were all the same variable measured under four experimental conditions, it’s a very plausible pattern.

Variance Components just means that each variance is different, and all covariances=0. So if all four variables were completely independent of each other and measured on different scales, that would be a reasonable pattern.

Unstructured just means there is no pattern at all. Each variance and each covariance is completely different and has no relation to the others.

There are many, many covariance structures. And each one makes sense in certain statistical situations. Until you’ve encountered those situations, they look crazy. But each one is just describing a pattern that makes sense in some situations.

There are three main ways you can approach analyzing repeated measures data, assuming the dependent variable is measured  continuously: repeated measures ANOVA, Mixed Models, and Marginal Models. Let’s take a look at how the three approaches differ and some of their advantages and disadvantages.

continuously: repeated measures ANOVA, Mixed Models, and Marginal Models. Let’s take a look at how the three approaches differ and some of their advantages and disadvantages.

For a few, very specific designs, you can get the exact same results from all three approaches. This makes it difficult to figure out what each one is doing, and how to apply them to OTHER designs.

For the sake of the current discussion, I will define repeated measures data as repeated measurements of the same outcome variable on the same individual. The individual is often a person, but could just as easily be a plant, animal, colony, company, etc. For simplicity, I’ll use “individual.” (more…)

This free, one-hour webinar is part of our regular Craft of Statistical Analysis series. In it, we will introduce and demonstrate two of the core concepts of mixed modeling—the random intercept and the random slope.

Most scientific fields now recognize the extraordinary usefulness of mixed models, but they’re a tough nut to crack for someone who didn’t receive training in their methodology.

But it turns out that mixed models are actually an extension of linear models. If you have a good foundation in linear models, the extension to mixed models is more of a step than a leap. (Okay, a large step, but still).

You’ll learn what random intercepts and slopes mean, what they do, and how to decide if one or both are needed. It’s the first step in understanding mixed modeling.

This webinar has already taken place. You can gain free access to a video recording of the webinar by completing the form below.

Here’s what participants said about the webinar:

“Thank you. I was also impressed with the way of explaining and the selection of example chosen to explain the theory.”

– Joanna Konieczna-Salamatin

“Teriffic job! I learned a lot. Thanks. Way to reduce a challenging topic to managable bite-size pieces. The graphical representations of the models helped me understand the random slope and random intercept terminology in a way I never got before.”

– Rob Baer

“I found it a great example and clear explanation, an hour is much better spent watching this than reading through a text book as an intro to this form of modeling.”

– Matt Cooper

“It was my first webinar and I was apprehensive with my lack of experience with the tecnology but it was really easy, user friendly, and definitely an experience to be repeated! Thank you!”

– Vanda Roque

” Just terrific. Clear, at the right level for me, extremely helpful.”

– Amy D’Andrade

“The seminar was well presented. The speaking was clear and easily undersood. The presentation was paced well. I found many of the questions and answers at the end to be *very* useful.”

– Andrew McLachlan

There are two ways to run a repeated measures analysis.The traditional way is to treat it as a multivariate test–each response is considered a separate variable.The other way is to it as a mixed model.While the multivariate approach is easy to run and quite intuitive, there are a number of advantages to running a repeated measures analysis as a mixed model.

First I will explain the difference between the approaches, then briefly describe some of the advantages of using the mixed models approach. (more…)