Every so often I point out to a client who exclusively uses menus in SPSS that they can (and should) hit the Paste button instead of OK. Many times, the client never realized it was there.

I am here today to tell you that it is there, and it is wonderful. For a few reasons.

When you use the menus in SPSS, you’re really taking a shortcut. You’re telling SPSS which syntax commands, along with which options, you want to run.

Clicking OK at the end of a dialog box will run the menu options you just picked. You may never see the underlying commands that SPSS just ran.

If instead you hit Paste, those command won’t automatically be run, but will instead the code to run those commands will be (more…)

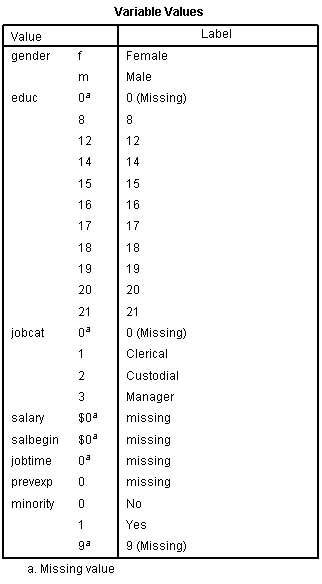

One of the nice features of SPSS is its ability to keep track of information on the variables themselves.

This includes variable labels, missing data codes, value labels, and variable formats. Spending the time to set up variable information makes data analysis much easier–you don’t have to keep looking up whether males are coded 1 or 0, for example.

And having them all in the variable view window makes things incredibly easy while you’re doing your analysis. But sometimes you need to just print them all out–to create a code book for another analyst or to include in the output you’re sending to a collaborator. Or even just to print them out for yourself for easy reference.

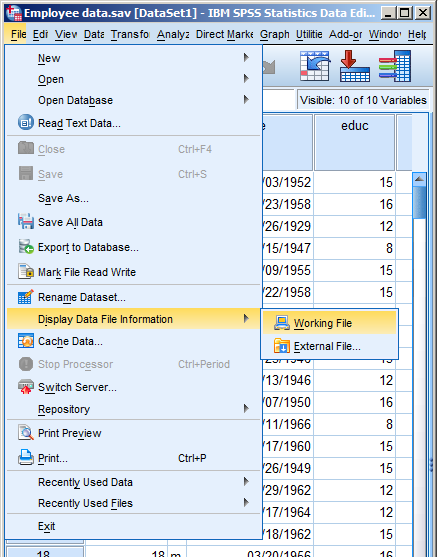

There is a nice little way to get a few tables with a list of all the variable metadata. It’s in the File menu. Simply choose Display Data File Information and Working File.

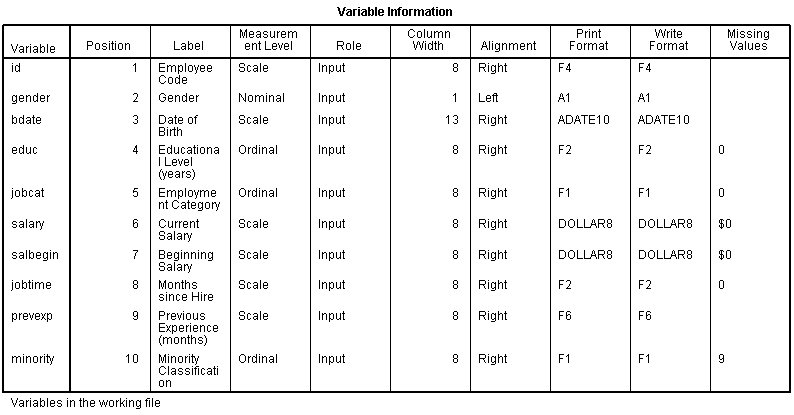

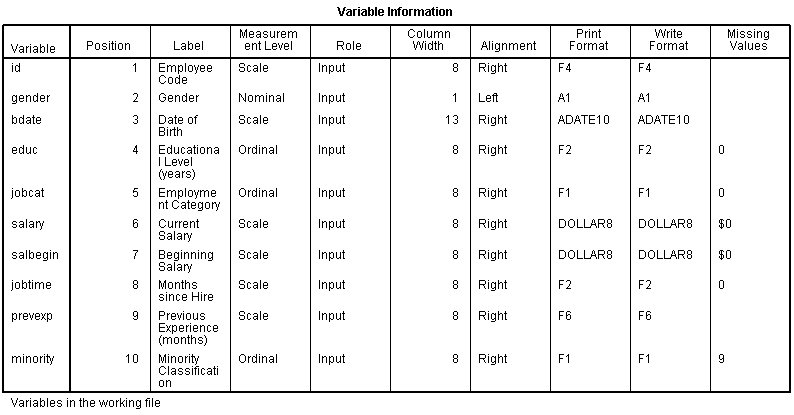

Doing this gives you two tables. The first includes the following information on the variables. I find the information I use the most are the labels and the missing data codes.

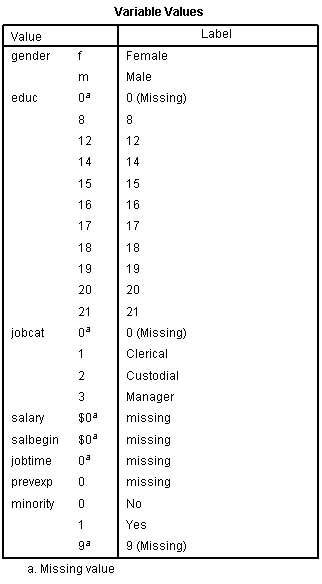

Even more useful, though, is the Value Label table.

It lists out the labels for all the values for each variable.

So you don’t have to remember that Job Category (jobcat) 1 is “Clerical,” 2 is “Custodial,” and 3 is “Managerial.”

It’s all right there.

Here’s a little SPSS tip.

When you create new variables, whether it’s through the Recode, Compute, or some other command, you need to check that it worked the way you think it did.

(As an aside, I hope this goes without saying, but never, never, never, never use Recode into Same Variable. Always Recode into Different Variable so you don’t overwrite your data and then discover you made a mistake. Or worse, not discover. It happens).

And the easiest way to do that is to simply look at the data. (more…)

by Annette Gerritsen, Ph.D.

In an earlier article I discussed how to do a cross-tabulation in SPSS. But what if you do not have a data set with the values of the two variables of interest?

For example, if you do a critical appraisal of a published study and only have proportions and denominators.

In this article it will be demonstrated how SPSS can come up with a cross table and do a Chi-square test in both situations. And you will see that the results are exactly the same.

‘Normal’ dataset

If you want to test if there is an association between two nominal variables, you do a Chi-square test.

In SPSS you just indicate that one variable (the independent one) should come in the row, (more…)

SPSS offers two choices under the recode command: Into Same Variable and Into Different Variables.

The command Into Same Variable replaces existing data with new values, but the command Into Different Variables adds a new variable to the data set.

In almost every situation, you want to use Into Different Variables. Recoding Into Same Variables replaces the values in the existing variable.

So if you notice a mistake after you’ve recoded, you can’t fix it.

But you may not even notice the mistake, because you can’t even test it.

And that’s just dangerous. (more…)

One of the places that SPSS syntax excels at efficiency is when you’re creating new variables. This is especially true when you’re creating a LOT of new variables, but even one or two can be quicker if you write the syntax code instead of menus.

And just as importantly, you’ll have documentation for exactly how you created them. (You think you’ll remember now, but 75 new variables later, you’ll thank me).

So once you create a new variable, you should of course immediately assign a Variable Label, and if appropriate, Value Labels and Missing Data Codes using Syntax.

Another thing that helps keep your new variable clean and interpretable is to assign the format. The default format is F8.2, which indicates a numerical value

You could go into the Variable View screen and manually change the Width and Decimals columns, which indicate how many characters go before and after (for numeric variables) the decimal point.

But why do all that when you can just use a single command to define multiple variables?

The syntax command is FORMATS. Here is the command for some common formats:

FORMATS NumVar1 NumVar2 (F5.0)

/NumVar3 (F6.1)

/StringVar1 (A15).

You can see the FORMATS command is followed by the variable names, then the format in parentheses.

Numeric variables NumVar1 and Numvar2 will both get the same format: with 5 digits, and nothing after the decimal.

Numeric variable NumVar3 will have 6 digits total, with one after the decimal.

And string variable (i.e. its value contain letters) StringVar1 is 15 characters wide.

This will get you started, but you can get all the specifics in the FORMATS section of the Command Syntax Reference, which is included in the SPSS help.

[Note: Edited explanation of F6.1 to be 6 digits total, not 6 digits before the decimal).