Have you ever compared the list of model assumptions for linear regression across two sources? Whether they’re textbooks, lecture  notes, or web pages, chances are the assumptions don’t quite line up.

notes, or web pages, chances are the assumptions don’t quite line up.

Why? Sometimes the authors use different terminology. So it just looks different.

And sometimes they’re including not only model assumptions, but inference assumptions and data issues. All are important, but understanding the role of each can help you understand what applies in your situation.

Model Assumptions

The actual model assumptions are about the specification and performance of the model for estimating the parameters well.

1. The errors are independent of each other

2. The errors are normally distributed

3. The errors have a mean of 0 at all values of X

4. The errors have constant variance

5. All X are fixed and are measured without error

6. The model is linear in the parameters

7. The predictors and response are specified correctly

8. There is a single source of unmeasured random variance

Not all of these are always explicitly stated. And you can’t check them all. How do you know you’ve included all the “correct” predictors?

But don’t skip the step of checking what you can. And for those you can’t, take the time to think about how likely they are in your study. Report that you’re making those assumptions.

Assumptions about Inference

Sometimes the assumption is not really about the model, but about the types of conclusions or interpretations you can make about the results.

These assumptions allow the model to be useful in answering specific research questions based on the research design. They’re not about how well the model estimates parameters.

Is this important? Heck, yes. Studies are designed to answer specific research questions. They can only do that if these inferential assumptions hold.

But if they don’t, it doesn’t mean the model estimates are wrong, biased, or inefficient. It simply means you have to be careful about the conclusions you draw from your results. Sometimes this is a huge problem.

But these assumptions don’t apply if they’re for designs you’re not using or inferences you’re not trying to make. This is a situation when reading a statistics book that is written for a different field of application can really be confusing. They focus on the types of designs and inferences that are common in that field.

It’s hard to list out these assumptions because they depend on the types of designs that are possible given ethics and logistics and the types of research questions. But here are a few examples:

1. ANCOVA assumes the covariate and the IV are uncorrelated and do not interact. (Important only in experiments trying to make causal inferences).

2. The predictors in a regression model are endogenous. (Important for conclusions about the relationship between Xs and Y where Xs are observed variables).

3. The sample is representative of the population of interest. (This one is always important!)

Data Issues that are Often Mistaken for Assumptions

And sometimes the list of assumptions includes data issues. Data issues are a little different.

They’re important. They affect how you interpret the results. And they impact how well the model performs.

But they’re still different. When a model assumption fails, you can sometimes solve it by using a different type of model. Data issues generally stay around.

That’s a big difference in practice.

Here are a few examples of common data issues:

1. Small Samples

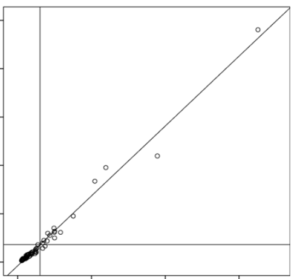

2. Outliers

3. Multicollinearity

4. Missing Data

5. Truncation and Censoring

6. Excess Zeros

So check for these data issues, deal with them if the solution doesn’t create more problems than you solved, and be careful with the inferences you draw when you can’t.

Go to the next article or see the full series on Easy-to-Confuse Statistical Concepts

When you’re model building, a key decision is which interaction terms to include. And which interactions to remove.

As a general rule, the default in regression is to leave them out. Add interactions only with a solid reason. It would seem like data fishing to simply add in all possible interactions.

And yet, that’s a common practice in most ANOVA models: put in all possible interactions and only take them out if there’s a solid reason. Even many software procedures default to creating interactions among categorical predictors.

(more…)

There are important ‘rules’ of statistical analysis. Like

- Always run descriptive statistics and graphs before running tests

- Use the simplest test that answers the research question and meets assumptions

- Always check assumptions.

But there are others you may have learned in statistics classes that don’t serve you or your analysis well once you’re working with real data.

When you are taking statistics classes, there is a lot going on. You’re learning concepts, vocabulary, and some really crazy notation. And probably a software package on top of that.

In other words, you’re learning a lot of hard stuff all at once.

Good statistics professors and textbook authors know that learning comes in stages. Trying to teach the nuances of good applied statistical analysis to students who are struggling to understand basic concepts results in no learning at all.

And yet students need to practice what they’re learning so it sticks. So they teach you simple rules of application. Those simple rules work just fine for students in a stats class working on sparkling clean textbook data.

But they are over-simplified for you, the data analyst, working with real, messy data.

Here are three rules of data analysis practice that you may have learned in classes that you need to unlearn. They are not always wrong. They simply don’t allow for the nuance involved in real statistical analysis.

The Rules of Statistical Analysis to Unlearn:

1. To check statistical assumptions, run a test. Decide whether the assumption is met by the significance of that test.

Every statistical test and model has assumptions. They’re very important. And they’re not always easy to verify.

For many assumptions, there are tests whose sole job is to test whether the assumption of another test is being met. Examples include the Levene’s test for constant variance and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, often used for normality. These tests are tools to help you decide if your model assumptions are being met.

But they’re not definitive.

When you’re checking assumptions, there are a lot of contextual issues you need to consider: the sample size, the robustness of the test you’re running, the consequences of not meeting assumptions, and more.

What to do instead:

Use these test results as one of many pieces of information that you’ll use together to decide whether an assumption is violated.

2. Delete outliers that are 3 or more standard deviations from the mean.

This is an egregious one. Really. It’s bad.

Yes, it makes the data look pretty. Yes, there are some situations in which it’s appropriate to delete outliers (like when you have evidence that it’s an error). And yes, outliers can wreak havoc on your parameter estimates.

But don’t make it a habit. Don’t follow a rule blindly.

Deleting outliers because they’re outliers (or using techniques like Winsorizing) is a great way to introduce bias into your results or to miss the most interesting part of your data set.

What to do instead:

When you find an outlier, investigate it. Try to figure out if it’s an error. See if you can figure out where it came from.

3. Check Normality of Dependent Variables before running a linear model

In a t-test, yes, there is an assumption that Y, the dependent variable, is normally distributed within each group. In other words, given the group as defined by X, Y follows a normal distribution.

In a t-test, yes, there is an assumption that Y, the dependent variable, is normally distributed within each group. In other words, given the group as defined by X, Y follows a normal distribution.

ANOVA has a similar assumption: given the group as defined by X, Y follows a normal distribution.

In linear regression (and ANCOVA), where we have continuous variables, this same assumption holds. But it’s a little more nuanced since X is not necessarily categorical. At any specific value of X, Y has a normal distribution. (And yes, this is equivalent to saying the errors have a normal distribution).

But here’s the thing: the distribution of Y as a whole doesn’t have to be normal.

In fact, if X has a big effect, the distribution of Y, across all values of X, will often be skewed or bimodal or just a big old mess. This happens even if the distribution of Y, at each value of X, is perfectly normal.

What to do instead:

Because normality depends on which Xs are in a model, check assumptions after you’ve chosen predictors.

Conclusion:

The best rule in statistical analysis: always stop and think about your particular data analysis situation.

If you don’t understand or don’t have the experience to evaluate your situation, discuss it with someone who does. Investigate it. This is how you’ll learn.

Of all the stressors you’ve got right now, accessing your statistical software from home shouldn’t be one of them. (You know, the one on your office computer).

We’ve gotten some updates from some statistical software companies on how they’re making it easier to access the software you have a license to or to extend a free trial while you’re working from home.

(more…)

One of the many decisions you have to make when model building is which form each predictor variable should take. One specific version of this decision is whether to combine categories of a categorical predictor.

decision is whether to combine categories of a categorical predictor.

The greater the number of parameter estimates in a model the greater the number of observations that are needed to keep power constant. The parameter estimates in a linear (more…)

Good graphs are extremely powerful tools for communicating quantitative information clearly and accurately.

Unfortunately, many of the graphs we see today confuse, mislead, or deceive the reader.

These poor graphs result from two key limitations. One is a graph designer who isn’t familiar with the principles of effective graphs. The other is software with a poor choice of default settings.

(more…)

notes, or web pages, chances are the assumptions don’t quite line up.

notes, or web pages, chances are the assumptions don’t quite line up.