One issue in data analysis that feels like it should be obvious, but often isn’t, is setting up your data.

The kinds of issues involved include:

- What is a variable?

- What is a unit of observation?

- Which data should go in each row of the data matrix?

Answering these practical questions is one of those skills that comes with experience, especially in complicated data sets.

Even so, it’s extremely important. If the data isn’t set up right, the software won’t be able to run any of your analyses.

And in many data situations, you will need to set up the data different ways for different parts of the analyses. (more…)

Are you learning Multilevel Models? Do you feel ready? Or in over your head?

It’s a very common analysis to need to use. I have to say, learning it is not so easy on your own. The concepts of random effects are hard to wrap your head around and there is a ton of new vocabulary and notation. Sadly, this vocabulary and notation is not consistent across articles, books, and software, so you end up having to do a lot of translating.

(more…)

When you learned analysis of variance (ANOVA), it’s likely that the emphasis was on the ANOVA table, with its Sums of Squares and F tests, followed by a post-hoc test. But ANOVA is quite flexible in how it can compare means. A large part of that flexibility comes from its ability to perform many types of statistical contrast.

That F test can tell you if there is evidence your categories are different from each other, which is a start. It is, however, only a start. Once you know at least some categories’ means are different, your next question is “How are they different?” This is what a statistical contrast can tell you.

What is a Statistical Contrast?

A statistical contrast is a comparison of a combination of the means of two or more categories. In practice, they are usually performed as a follow up to the ANOVA F test. Most statistical programs include contrasts as an optional part of ANOVA analysis. (more…)

The classic way to compare means in analysis of variance is examining pairwise differences in means after an F test.. It’s great for many problems, but sometimes your research question isn’t about pairwise differences.

Pairwise differences are not ideal if your research question is if, like the Sesame Street song, one of these groups is not like the others. Perhaps, you are trying to assure that groups conform to a common standard. Analysis of Means (ANOM) helps in all these settings. (more…)

Designing experiments would always be simple if we could just randomly assign subjects to different treatment conditions with no other restrictions. Unfortunately, that doesn’t always work.

For example, there are many experimental situations where the subjects aren’t independent of each other. The subjects that are related to each other are combined into clusters called “blocks.” It can happen due to practicalities of running an experiment efficiently or you can intentionally plan it as a way to reduce random variance.

In either case, this is a randomized complete block design. It’s a great design to become familiar with because it will greatly expand your ability to create and analyze experiments.

How It Works

When you have subjects that share characteristics with one another, it can sometimes be difficult to isolate those characteristics directly. This makes it hard to record them as additional variables. By identifying the subjects that are similar, you can still capture how those characteristics affect the outcome. Subjects that are similar are grouped into “blocks.”

From there, you can make treatment assignments so that you put subjects from the same block into different treatment groups.

Why different treatment groups? Suppose subjects from the same block were assigned to the same treatment group. (more…)

If you have a categorical predictor variable that you plan to use in a regression analysis in SPSS, there are a couple ways to do it.

If you have a categorical predictor variable that you plan to use in a regression analysis in SPSS, there are a couple ways to do it.

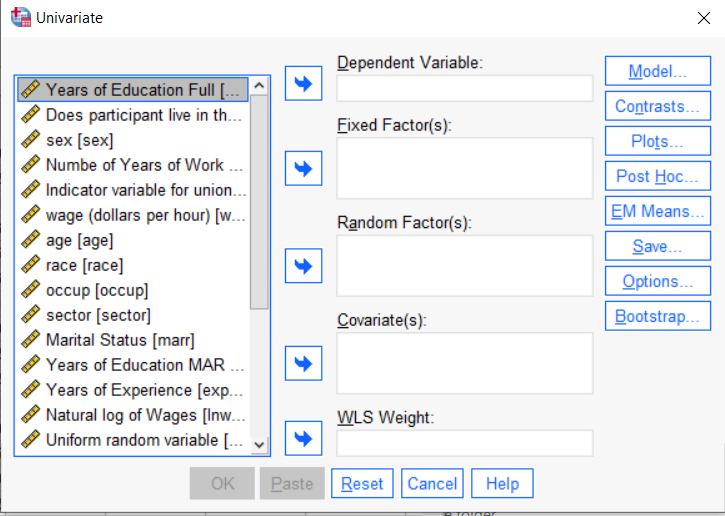

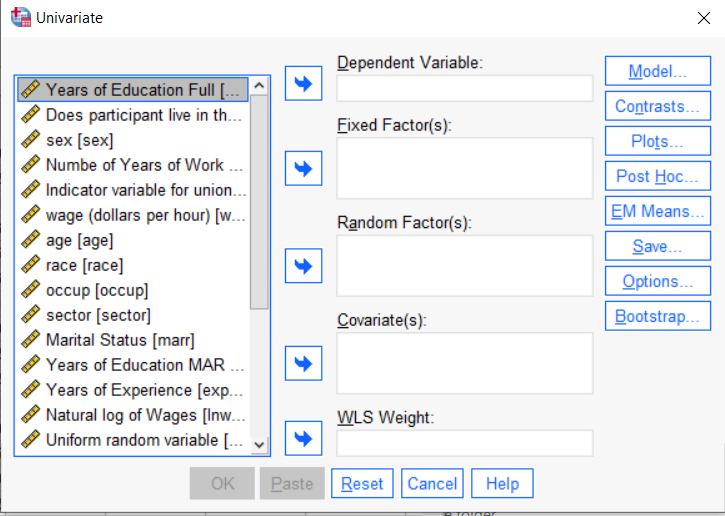

You can use the SPSS Regression procedure. Or you can use SPSS General Linear Model–>Univariate, which I discuss here. If you use Syntax, it’s the UNIANOVA command.

The big question in SPSS GLM is what goes where. As I’ve detailed in another post, any continuous independent variable goes into covariates. And don’t use random factors at all unless you really know what you’re doing.

So the question is what to do with your categorical variables. You have two choices, and each has advantages and disadvantages.

The easiest is to put categorical variables in Fixed Factors. SPSS GLM will dummy code those variables for you, which is quite convenient if your categorical variable has more than two categories.

However, there are some defaults you need to be aware of that may or may not make this a good choice.

The dummy coding reference group default

SPSS GLM always makes the reference group the one that comes last alphabetically.

So if the values you input are strings, it will be the one that comes last. If those values are numbers, it will be the highest one.

Not all procedures in SPSS use this default so double check the default if you’re using something else. Some procedures in SPSS let you change the default, but GLM doesn’t.

In some studies it really doesn’t matter which is the reference group.

But in others, interpreting regression coefficients will be a whole lot easier if you choose a group that makes a good comparison such as a control group or the most common group in the data.

If you want that to be the reference group in SPSS GLM, make it come last alphabetically. I’ve been known to do things like change my data so that the control group becomes something like ZControl. (But create a new variable–never overwrite original data).

It really can get confusing, though, if the variable was already dummy coded–if it already had values of 0 and 1. Because 1 comes last alphabetically, SPSS GLM will make that group the reference group and internally code it as 0.

This can really lead to confusion when interpreting coefficients. It’s not impossible if you’re paying attention, but you do have to pay attention. It’s generally better to recode the variable so that you don’t confuse yourself. And while you may believe you’re up for overcoming the confusion, why make things harder on yourself or with any other colleague you’re sharing results with?

Interactions among fixed factors default

There is another key default to keep in mind. GLM will automatically create interactions between any and all variables you specify as Fixed Factors.

If you put 5 variables in Fixed Factors, you’ll get a lot of interactions. SPSS will automatically create all 2-way, 3-way, 4-way, and even a 5-way interaction among those 5 variables.

That’s a lot of interactions.

In contrast, GLM doesn’t create by default any interactions between Covariates or between Covariates and Fixed Factors.

So you may find you have more interactions than you wanted among your categorical predictors. And fewer interactions than you wanted among numerical predictors.

There is no reason to use the default. You can override it quite easily.

Just click on the Model button. Then choose “Custom Model.” You can then choose which interactions you do, or don’t, want in the model.

If you’re using SPSS syntax, simply add the interactions you want to the /Design subcommand.

So think about which interactions you want in the model. And take a look at whether your variables are already dummy coded.