Have you ever compared the list of model assumptions for linear regression across two sources? Whether they’re textbooks, lecture  notes, or web pages, chances are the assumptions don’t quite line up.

notes, or web pages, chances are the assumptions don’t quite line up.

Why? Sometimes the authors use different terminology. So it just looks different.

And sometimes they’re including not only model assumptions, but inference assumptions and data issues. All are important, but understanding the role of each can help you understand what applies in your situation.

Model Assumptions

The actual model assumptions are about the specification and performance of the model for estimating the parameters well.

1. The errors are independent of each other

2. The errors are normally distributed

3. The errors have a mean of 0 at all values of X

4. The errors have constant variance

5. All X are fixed and are measured without error

6. The model is linear in the parameters

7. The predictors and response are specified correctly

8. There is a single source of unmeasured random variance

Not all of these are always explicitly stated. And you can’t check them all. How do you know you’ve included all the “correct” predictors?

But don’t skip the step of checking what you can. And for those you can’t, take the time to think about how likely they are in your study. Report that you’re making those assumptions.

Assumptions about Inference

Sometimes the assumption is not really about the model, but about the types of conclusions or interpretations you can make about the results.

These assumptions allow the model to be useful in answering specific research questions based on the research design. They’re not about how well the model estimates parameters.

Is this important? Heck, yes. Studies are designed to answer specific research questions. They can only do that if these inferential assumptions hold.

But if they don’t, it doesn’t mean the model estimates are wrong, biased, or inefficient. It simply means you have to be careful about the conclusions you draw from your results. Sometimes this is a huge problem.

But these assumptions don’t apply if they’re for designs you’re not using or inferences you’re not trying to make. This is a situation when reading a statistics book that is written for a different field of application can really be confusing. They focus on the types of designs and inferences that are common in that field.

It’s hard to list out these assumptions because they depend on the types of designs that are possible given ethics and logistics and the types of research questions. But here are a few examples:

1. ANCOVA assumes the covariate and the IV are uncorrelated and do not interact. (Important only in experiments trying to make causal inferences).

2. The predictors in a regression model are endogenous. (Important for conclusions about the relationship between Xs and Y where Xs are observed variables).

3. The sample is representative of the population of interest. (This one is always important!)

Data Issues that are Often Mistaken for Assumptions

And sometimes the list of assumptions includes data issues. Data issues are a little different.

They’re important. They affect how you interpret the results. And they impact how well the model performs.

But they’re still different. When a model assumption fails, you can sometimes solve it by using a different type of model. Data issues generally stay around.

That’s a big difference in practice.

Here are a few examples of common data issues:

1. Small Samples

2. Outliers

3. Multicollinearity

4. Missing Data

5. Truncation and Censoring

6. Excess Zeros

So check for these data issues, deal with them if the solution doesn’t create more problems than you solved, and be careful with the inferences you draw when you can’t.

Go to the next article or see the full series on Easy-to-Confuse Statistical Concepts

In your statistics class, your professor made a big deal about unequal sample sizes in one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for two reasons.

1. Because she was making you calculate everything by hand. Sums of squares require a different formula* if sample sizes are unequal, but statistical software will automatically use the right formula. So we’re not too concerned. We’re definitely using software.

2. Nice properties in ANOVA such as the Grand Mean being the intercept in an effect-coded regression model don’t hold when data are unbalanced. Instead of the grand mean, you need to use a weighted mean. That’s not a big deal if you’re aware of it. (more…)

Mean imputation: So simple. And yet, so dangerous.

Perhaps that’s a bit dramatic, but mean imputation (also called mean substitution) really ought to be a last resort.

It’s a popular solution to missing data, despite its drawbacks. Mainly because it’s easy. It can be really painful to lose a large part of the sample you so carefully collected, only to have little power.

But that doesn’t make it a good solution, and it may not help you find relationships with strong parameter estimates. Even if they exist in the population.

On the other hand, there are many alternatives to mean imputation that provide much more accurate estimates and standard errors, so there really is no excuse to use it.

This post is the first explaining the many reasons not to use mean imputation (and to be fair, its advantages).

First, a definition: mean imputation is the replacement of a missing observation with the mean of the non-missing observations for that variable.

Problem #1: Mean imputation does not preserve the relationships among variables.

True, imputing the mean preserves the mean of the observed data. So if the data are missing completely at random, the estimate of the mean remains unbiased. That’s a good thing.

Plus, by imputing the mean, you are able to keep your sample size up to the full sample size. That’s good too.

This is the original logic involved in mean imputation.

If all you are doing is estimating means (which is rarely the point of research studies), and if the data are missing completely at random, mean imputation will not bias your parameter estimate.

It will still bias your standard error, but I will get to that in another post.

Since most research studies are interested in the relationship among variables, mean imputation is not a good solution. The following graph illustrates this well:

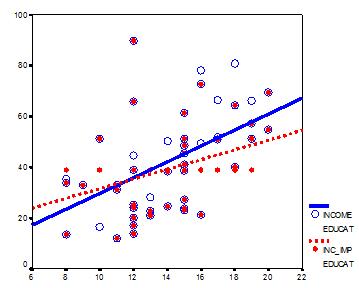

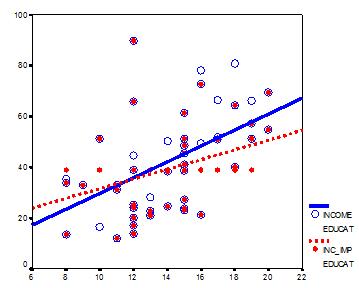

This graph illustrates hypothetical data between X=years of education and Y=annual income in thousands with n=50. The blue circles are the original data, and the solid blue line indicates the best fit regression line for the full data set. The correlation between X and Y is r = .53.

I then randomly deleted 12 observations of income (Y) and substituted the mean. The red dots are the mean-imputed data.

Blue circles with red dots inside them represent non-missing data. Empty Blue circles represent the missing data. If you look across the graph at Y = 39, you will see a row of red dots without blue circles. These represent the imputed values.

The dotted red line is the new best fit regression line with the imputed data. As you can see, it is less steep than the original line. Adding in those red dots pulled it down.

The new correlation is r = .39. That’s a lot smaller that .53.

The real relationship is quite underestimated.

Of course, in a real data set, you wouldn’t notice so easily the bias you’re introducing. This is one of those situations where in trying to solve the lowered sample size, you create a bigger problem.

One note: if X were missing instead of Y, mean substitution would artificially inflate the correlation.

In other words, you’ll think there is a stronger relationship than there really is. That’s not good either. It’s not reproducible and you don’t want to be overstating real results.

This solution that is so good at preserving unbiased estimates for the mean isn’t so good for unbiased estimates of relationships.

Problem #2: Mean Imputation Leads to An Underestimate of Standard Errors

A second reason is applies to any type of single imputation. Any statistic that uses the imputed data will have a standard error that’s too low.

In other words, yes, you get the same mean from mean-imputed data that you would have gotten without the imputations. And yes, there are circumstances where that mean is unbiased. Even so, the standard error of that mean will be too small.

Because the imputations are themselves estimates, there is some error associated with them. But your statistical software doesn’t know that. It treats it as real data.

Ultimately, because your standard errors are too low, so are your p-values. Now you’re making Type I errors without realizing it.

That’s not good.

A better approach? There are two: Multiple Imputation or Full Information Maximum Likelihood.

When you’re model building, a key decision is which interaction terms to include. And which interactions to remove.

As a general rule, the default in regression is to leave them out. Add interactions only with a solid reason. It would seem like data fishing to simply add in all possible interactions.

And yet, that’s a common practice in most ANOVA models: put in all possible interactions and only take them out if there’s a solid reason. Even many software procedures default to creating interactions among categorical predictors.

(more…)

Most of the time when we plan a sample size for a data set, it’s based on obtaining reasonable statistical power for a key analysis of that data set. These power calculations figure out how big a sample you need so that a certain width of a confidence interval or p-value will coincide with a scientifically meaningful effect size.

But that’s not the only issue in sample size, and not every statistical analysis uses p-values.

(more…)

notes, or web pages, chances are the assumptions don’t quite line up.

notes, or web pages, chances are the assumptions don’t quite line up.