Censored data are inherent in any analysis, like Event History or Survival Analysis, in which the outcome measures the Time to Event TTE. Censoring occurs when the event doesn’t occur for an observed individual during the time we observe them.

Despite the name, the event of “survival” could be any categorical event that you would like to describe the mean or median TTE. To take the censoring into account, though, you need to make sure your data are set up correctly.

Here is a simple example, for a data set that measures days after surgery until an (more…)

Time to event analyses (aka, Survival Analysis and Event History Analysis) are used often within medical, sales and epidemiological research. Some examples of time-to-event analysis are measuring the median time to death after being diagnosed with a heart condition, comparing male and female time to purchase after being given a coupon and estimating time to infection after exposure to a disease.

Survival time has two components that must be clearly defined: a beginning point and an endpoint that is reached either when the event occurs or when the follow-up time has ended.

One basic concept needed to understand time-to-event (TTE) analysis is censoring.

In simple TTE, you should have two types of observations:

1. The event occurred, and we are able to measure when it occurred OR

2. The event did NOT occur during the time we observed the individual, and we only know the total number of days in which it didn’t occur. (CENSORED).

Again you have two groups, one where the time-to-event is known exactly and one where it is not. The latter group is only known to have a certain amount of time where the event of interest did not occur. We don’t know if it would have occurred had we observed the individual longer. But knowing that it didn’t occur for so long tells us something about the risk of the envent for that person.

For example, let the time-to-event be a person’s age at onset of cancer. If you stop following someone after age 65, you may know that the person did NOT have cancer at age 65, but you do not have any information after that age.

You know that their age of getting cancer is greater than 65. But you do not know if they will never get cancer or if they’ll get it at age 66, only that they have a “survival” time greater than 65 years. They are censored because we did not gather information on that subject after age 65.

So one cause of censoring is merely that we can’t follow people forever. At some point you have to end your study, and not all people will have experienced the event.

But another common cause is that people are lost to follow-up during a study. This is called random censoring. It occurs when follow-up ends for reasons that are not under control of the investigator.

In survival analysis, censored observations contribute to the total number at risk up to the time that they ceased to be followed. One advantage here is that the length of time that an individual is followed does not have to be equal for everyone. All observations could have different amounts of follow-up time, and the analysis can take that into account.

Allison, P. D. (1995). Survival Analysis Using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Hosmer, D. W. (2008). Applied Survival Analysis (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

by Annette Gerritsen, Ph.D.

Cross-tabulation in cohort studies

Assume you have just done a cohort study. How do you actually do the cross-tabulation to calculate the cumulative incidence in both groups?

Best is to always put the outcome variable (disease yes/no) in the columns and the exposure variable in the rows. In other words, put the dependent variable–the one that describes the problem under study–in the columns. And put the independent variable–the factor assumed to cause the problem–in the rows.

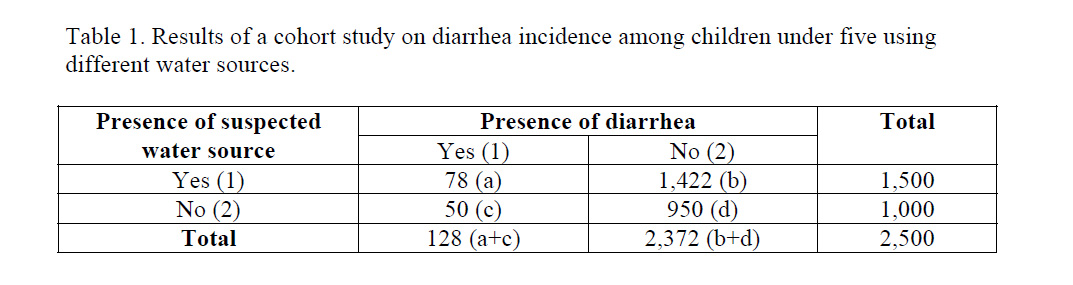

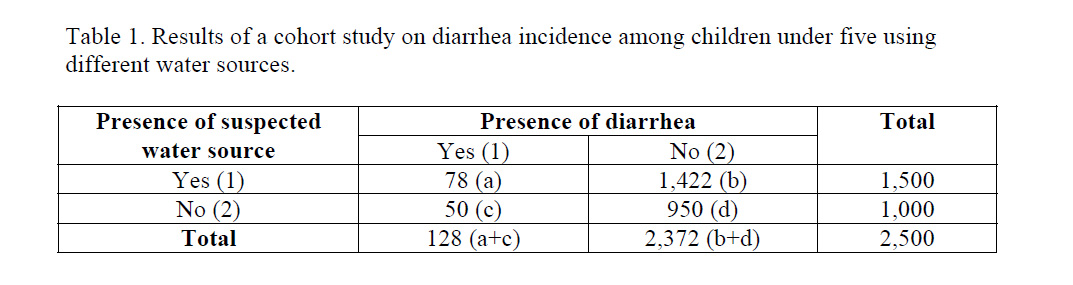

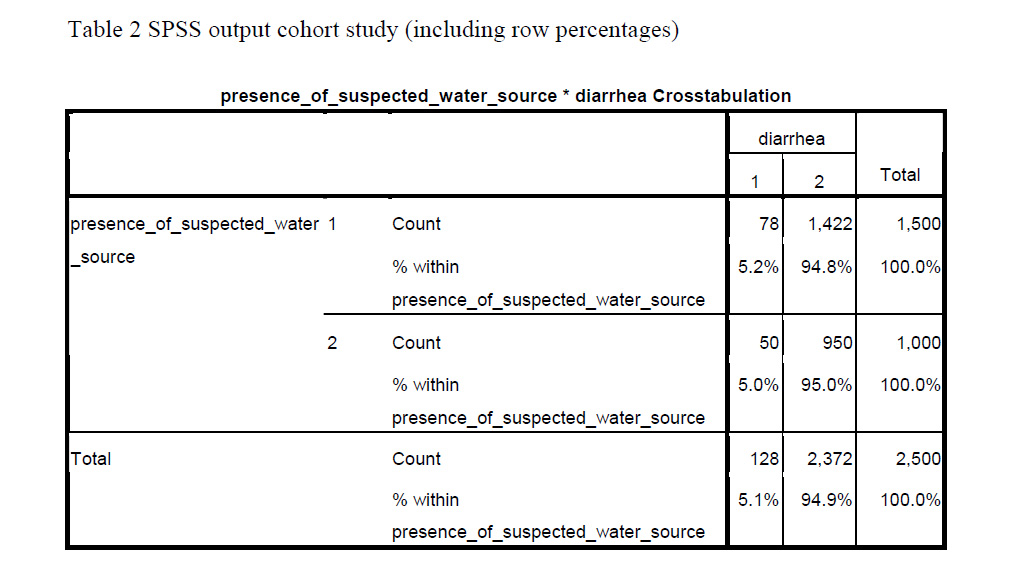

Let’s take as example a cohort study used to see whether there is a causal relationship between the use of a certain water source and the incidence of diarrhea among children under five in a village with different water sources. In this case, the variable diarrhea (yes/no) should be in the columns. The variable water source (suspected/other) should be in the rows.

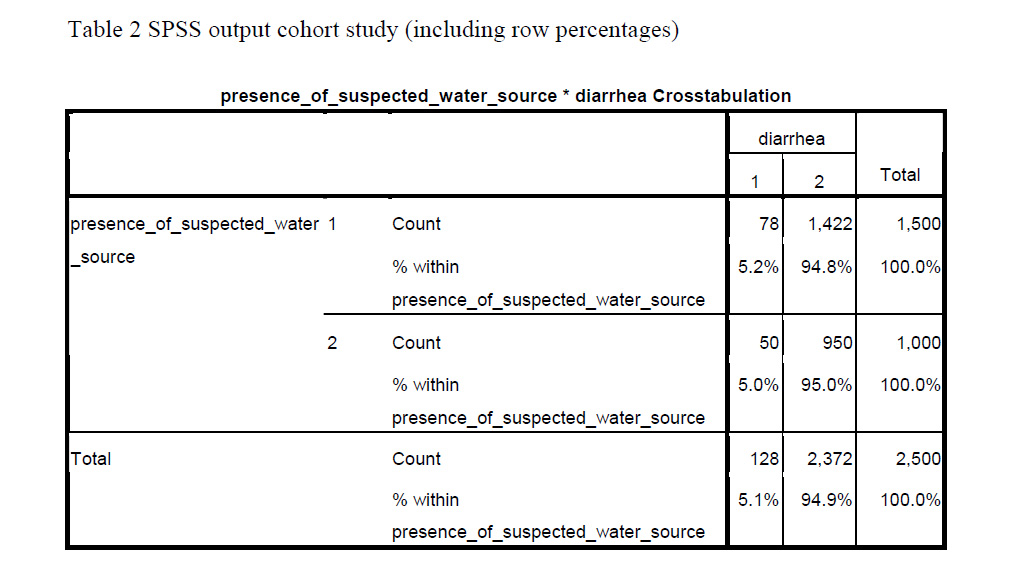

SPSS will put the lowest value of the variable in the first column or row. So in order to get those with diarrhea in the first column you should label ‘diarrhea’ as 1 and ‘no diarrhea’ as 2. The same is true for the exposure variable: label the ‘suspected water source’ as 1 and the ‘other water source’ as 2.

You will then be able to calculate the cumulative incidence (risk of developing the disease) among those with the exposure: a / (a + b) and among those without the exposure: c / (c + d).

In the case of the diarrhea study (Table 1), you could calculate the cumulative incidence of diarrhea among those exposed to the suspected water source, which would be (78 / 1,500 =) 5.2%.

You can also do this for those exposed to other water sources, which would be (50 / 1,000 =) 5.0%.

SPSS can give you these percentages immediately (in cell ‘a’ and ‘c’ respectively), when you ask to display row percentages in the Cells option (Table 2).

Cross-tabulation in Case-Control Studies

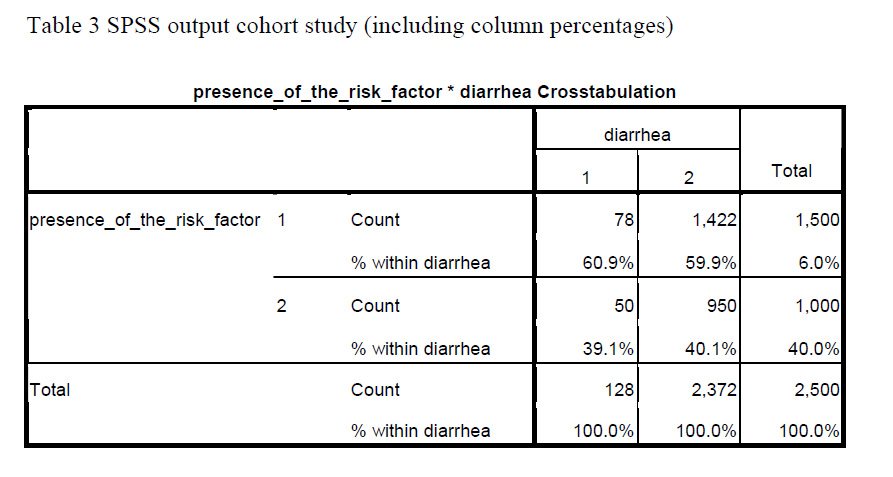

When you have used a case-control design for the diarrhea study, the actual cross-tabulation is quite similar, only “presence of diarrhea yes/no”, is now changed into “cases” and “controls.

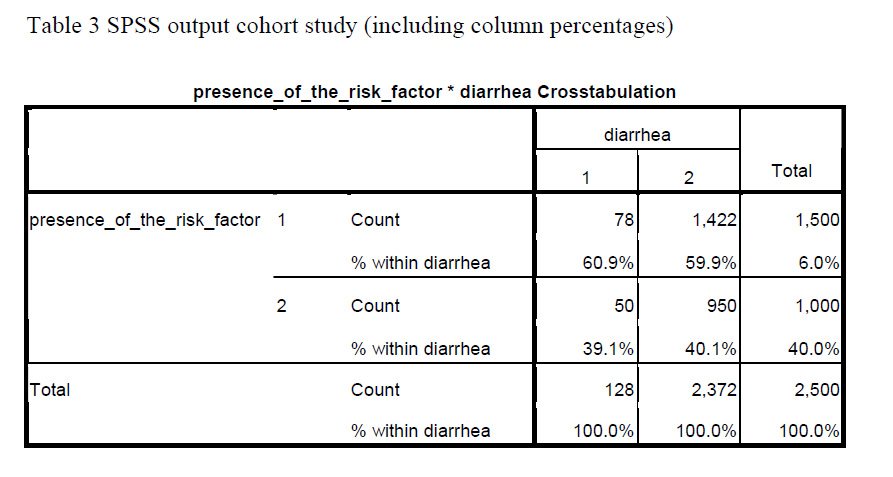

Label the cases as 1, and the controls as 2. Be aware that row percentages have no meaning in terms of occurrence of disease in case-control studies. This is because in case-control studies the researcher determines how many patients and how many controls are included.

The ratio between the number of patients and controls (e.g. 2 : 1 or 4 : 1) influences the row percentages. So in a case-control study, the cumulative incidence cannot be calculated.

When having conducted a case-control study, you can ask to display column percentages. That gives you the proportion of those exposed to the suspected water source among the cases (in cell ‘a’) and among the controls (in cell ‘b’).

Table 3 gives the SPSS output for the same diarrhea study assuming that it had a case-control design. Using the data provided, (78 / 128 =) 60.9% of the cases were exposed to the suspected water source, while this was (1,422 / 2,372 =) 59.9% of the controls (asked for column percentages).

Another article will be devoted to measures of association: How do you actually compare cumulative incidence rates in cohort studies? And what measure of association can be used in case-control studies?

About the Author: With expertise in epidemiology, biostatistics and quantitative research projects, Annette Gerritsen, Ph.D. provides services to her clients focussing on the methodological soundness of each phase of an epidemiological study to ensure getting valid answers to the proposed research questions. She is the founder of Epi Result.

Two designs commonly used in epidemiology are the cohort and case-control studies. Both study causal relationships between a risk factor and a disease. What is the difference between these two designs? And when should you opt for the one or the other?

Cohort studies

Cohort studies begin with a group of people (a cohort) free of disease. The people in the cohort are grouped by whether or not they are exposed to a potential cause of disease. The whole cohort is followed over time to see if (more…)

by Ursula Saqui, Ph.D.

This is the second post of a two-part series on the overall process of doing a literature review. Part one discussed the benefits of doing a literature review, how to get started, and knowing when to stop.

You have made a commitment to do a literature review, have the purpose defined, and are ready to get started.

Where do you find your resources?

If you are not in academia, have access to a top-notch library, or receive the industry publications of interest, you may need to get creative if you do not want to pay for each article. (In a pinch, I have paid up to $36 for an article, which can add up if you are conducting a comprehensive literature review!)

Here is where the internet and other community resources can be your best friends.

- Know the difference between Google and Google Scholar. Google is helpful for popular mainstream publications whereas Google Scholar focuses only on scholarly references such as articles, theses, books, abstracts, and court opinions that are written by academics and other professional scholars.

- ResearchGATE is an example of a collaborative scientific community that indexes articles. Many times you can find the full text of articles at no charge.

- Your state may offer access to different databases for its residents. For example, in my home state of Indiana, residents have access to Inspire, a collection of resources, databases, and government publications. Click here to see if your state offers a similar resource.

- Check your local community library. They may not have the resources you need but they can often get them through inter-library loan. For example, my local community library does not carry advanced statistics books but the librarians can get them for me via their borrowing privileges with universities.

- Even without access to a specific database, you can search thousands of government sponsored research reports that have been conducted by the U.S. government or one of its affiliates. For example, in completing a literature review of service learning programs, I found a government report that summarized 10 years of research in service learning. (That made my day!)

- Private foundations or research companies may also conduct high-quality peer-reviewed research. For example, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation conducts and disseminates research on issues related to health and health care.

- If you know who authored the article, you can sometimes find a pdf file of their article on their website or university website listed under their vita or recent publications.

- Try to contact the author directly. When I have contacted authors, they have graciously sent me a complimentary copy of their article.

Still stuck? Hire someone who knows how to do a good literature review and has access to quality resources.

On a budget? Hire a student who has access to an academic library. Many times students can get credit for working on research and business projects through internships or experiential learning programs. This situation is a win-win. You get the information you need and the student gets academic credit along with exposure to new ideas and topics.

About the Author: With expertise in human behavior and research, Ursula Saqui, Ph.D. gives clarity and direction to her clients’ projects, which inevitably lead to better results and strategies. She is the founder of Saqui Research.

by Ursula Saqui, Ph.D.

This post is the first of a two-part series on the overall process of doing a literature review. Part two covers where to find your resources.

Would you build your house without a foundation? Of course not! However, many people skip the first step of any empirical-based project–conducting a literature review. Like the foundation of your house, the literature review is the foundation of your project.

Having a strong literature review gives structure to your research method and informs your statistical analysis. If your literature review is weak or non-existent, (more…)